The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.

John Maynard Keynes

![]()

Adding perspective is a large part of our job at Iron Capital. We are often asked to share our views on issues not directly related to investing; other times we are asked about a specific investment opportunity. To that end, we share these thoughts on our blog, appropriately titled, “Perspectives.”

We must reject theories that cannot be backed up by facts, but we must also reject facts that cannot be explained by any theory. It isn’t enough to just know the data; one must also know the why of the data. If one can’t figure out the why, then the data should be noted as a mere coincidence. Theory matters.

Who wants to get more for less? I know what you are thinking: Who doesn’t want to get more for less? Evidently one answer is Peter Navarro, and any other economist who believes that a trade deficit is a bad thing. For those who are less familiar, Mr. Navarro is one of President Trump’s advisers…

Love him or hate him, but either way you have to admit Donald Trump has style. He doesn’t just build hotels; he builds hotels with his name plastered on them in huge gold letters. He has been this way his whole life, so he is not just going to quietly go about the business of rightsizing government…

The “dealings of my trade” are to maximize the financial welfare of our clients. Maximizing economic growth is part of that equation, which means when I discuss economic policies I will point out when they actually hurt the economy, and that is what gets me in trouble.

I might be in the minority here, but this presidential election season seems more taxing than most. I really wish there was an interesting, or even realistic, tax proposal I could dissect for you all, but nope. All we are getting is “red meat” for the bases. The Harris proposal includes raising corporate taxes. This…

Milton Friedman’s contribution to economics is often misunderstood. He is most remembered for his public defense of capitalism, and for good reason. He had a wonderful way of explaining basic economics in a way the average person can understand. However, you didn’t win Nobel Prizes back then for simply explaining economics to the masses.

Friedman was among the first to bring serious quantitative analysis to the field of economics. Prior to Friedman, the field was largely an exercise in logic. He was one of the pioneers of the type of analysis that the world of sports calls analytics. He didn’t just make a logical argument for economic policy; he proved his theories with data. He also provided one of the greatest lessons for the use of data to prove or disprove theories: He said one must reject theories that cannot be backed up by facts. That part is easy. He also said you should reject facts that cannot be explained by theory.

In other words, it isn’t enough to just know the data, one must also know the why of the data. If one can’t figure out the why, then the data should be noted as a mere coincidence. So, what does this have to do with Alabama and Duke playing in the Elite 8 of the NCAA Tournament last weekend?

Analytics has become crucial to modern sports, and Nate Oats, head coach of Alabama’s men’s basketball team, is one of the most notable disciples. In basketball the numbers say that a team should take shots from the three-point range and from point blank range – three-pointers and layups. The shots in the middle, the mid-range shots, should be avoided. The reason is simple math: Layups are desirable because they can be made at a very high percentage.

Three-pointers are desirable because three is greater than two, the value of normal shots – actually 50 percent greater. The shots in the middle are not desirable because they are worth only two points and harder to make than layups. Many modern coaches have said no to mid-range shots, and Nate Oats is among the most outspoken on this subject. He will tell you it is just math, and facts don’t lie. So why did these mid-range shots used to be so prevalent in the game? Young coaches seem to believe it is because those who went before could not count to three.

Actually, it has to do with this thing called defense. The other team is allowed to try to stop you from scoring. They also teach math at Duke. Duke came in with a strategy: chase them off the three-point line and let their seven-foot two-inch center block the layups. Duke knew they didn’t have to guard the middle because the analytics department took care of that for them. It is a fact that three-pointers and layups are the best shots, but what is the theory behind eliminating one of the three ways to score from your offense?

When pressed on tariffs, the Trump administration often points to the late 19th century when the United States did not have an income tax and tariffs were a primary source of revenue for the federal government. This was a period of great economic expansion. That is a fact: We had high levels of tariffs and great economic success.

This was a period defined by the industrialization of the U.S., the rebuilding of the South, and great Westward expansion. In other words, this was a time when there would have been economic expansion regardless of domestic tax policy. What is the theory of how tariffs actually contributed to this success? There isn’t one.

We must reject theories that cannot be backed up by facts, but we must also reject facts that cannot be explained by any theory. The theory of good basketball offense is to take what the defense gives you and be able to score at all three levels. Duke is really good and they might have won anyway, but had Alabama attacked them in the midrange, they would have been closer and very likely opened up either the basket or the three-point line. Theory matters.

Tariffs were prevalent in the 19th century and we did okay; They were pushed hard in 1930 and brought on the Great Depression. Both of those are facts, but only one can be explained by any logical theory. Theory matters, at least that is my perspective.

Warm regards,

Chuck Osborne, CFA

~What the Alabama-Duke basketball game teaches us about tariffs

Who wants to get more for less? I know what you are thinking: Who doesn’t want to get more for less? Evidently one answer is Peter Navarro, and any other economist who believes that a trade deficit is a bad thing. For those who are less familiar, Mr. Navarro is one of President Trump’s advisers and the one most responsible for Trump’s idea that tariff is a “beautiful word.”

The new administration is moving so fast on seemingly every front that it is hard to keep up. However, our modern economy reacts quickly these days. Just last week the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow measure of real-time GDP was saying the economy was growing at 2.3 percent. As I write, the same measure says the economy is shrinking at a rate of 2.8 percent. Yes, we have gone from +2.3 to -2.8. That is an enormous change in a very short time; what could be the cause?

The largest factor in that sudden reversal of fortunes is net exports (in other words, exports minus imports), which fell to -3.70 from -0.41. In plain English, we have imported a lot more stuff thus far this year. Most likely people are trying to get their foreign goods before tariffs go into effect. This means the so-called trade deficit has exploded, and in the mathematical calculation of GDP, that is input as a negative. As a result, some, including Navarro, will argue that having a trade deficit – importing more than you export – is a bad thing. But is it?

Before answering that question, I think it is important to understand why we subtract imports from GDP. Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, is a measure of everything that is produced domestically, so by definition we do not wish to count items produced in other countries. So, what we want is for imports to not be counted one way or the other. The natural reaction to that desire might be to not count them at all, but there is a problem with that: The main item in the GDP calculation is consumption. When one goes to her local Toyota dealer and purchases a new car, that is measured as consumption. The money spent on that car was produced domestically, and much that goes into the transaction is also domestic. The car itself was imported from Japan. So, we subtract the car from GDP because it was captured in consumption, and we don’t want it to be in the calculation one way or the other.

In the real world, imports do not subtract from domestic production. They also do not add to production; they are simply neutral. To reflect that in the GDP calculation, they must be subtracted. Navarro would argue that if we didn’t buy that car from Japan, then we would have bought one made here. That could be true, but is that actually a better outcome?

The best way to understand macroeconomic issues, such as trade, is to remember that the macroeconomy is nothing more, or less, than all of our microeconomies put together. So, do you make everything you consume? Would you be better off if you did?

The answer to the first question is an obvious no. If that were not the case, you would not be reading this. You would either be cleaning your cave or hunting your dinner. My family has the good fortune of knowing the answer to the next question. My wife’s grandfather built a hunting camp in the Shenandoah Valley region in Virginia 75 years ago. We still enjoy using it to this day. There is a simple cabin that does provide good shelter, electricity, running water, and indoor plumbing. Heat is provided by a fireplace and a wood stove. Meals can be prepared on the wood stove or the charcoal grill outside. We stop and get groceries a little more than an hour from the camp, and we lose cell coverage about 30 minutes out. Modern satellite devices such as Starlink still do not work there for reasons that are not clear to us.

When we are there, we are completely on our own and can rely only on what we brought in. It is a great escape for a few days. Then, you realize that having to chop wood so we can have dinner means starting not long after lunch. An entire day can be spent just doing the necessary work to put the next meal on the table. We have deep conversations about how our ancestors even survived and eventually feel the longing to make the hour-long trip for a civilization break to check in with the outside world and eat in a restaurant. The best two restaurants in the closest real town are Mexican and Italian. Yes, the word “best” is relative, and that should speak volumes about whether we would be better off without trading with other countries and other cultures.

I have spent my entire adult life helping others reach their financial goals. I could simplify those down to having the biggest personal trade deficit possible: It is our human desire to do only the things we really want to do and to allow someone else to do everything else for us. We work our jobs for the purpose of gaining money to pay for the things we don’t have the time or desire to do for ourselves. We ultimately plan on retiring, at which time our personal trade deficit will equal 100 percent of our consumption.

The more financially successful people are, the larger their personal trade deficits. I guarantee you that Donald Trump’s personal trade deficit is enormous. I will wager my entire net worth that he doesn’t mow the grass at Mar-a-Lago. Does he believe that his grounds crew (I am positive it requires a crew) is taking advantage of him by denying him the ability to mow his own lawn? Does he think he is a loser because his personal trade deficit is far larger than 99 percent of people in the world?

Of course not. When we bring it down to the personal level, the answer becomes obvious. We are made richer by trade, not poorer. When we run large trade deficits we are winning, not losing. We are getting more for less.

The economic data backs this up. Trade deficits expand during economic expansions and shrink during recessions. What about the countries that do not fight fair? The ones who subsidize their manufacturing. Once again, take it down to the personal level. If a grounds crew is willing to work for less than market rates, then who is taking advantage of whom?

What about the manufacturing jobs in the U.S.? We have to be honest: manufacturing as a percentage of real GDP has held steady in this country since 1947. There is no decline in manufacturing. Have factories closed in the rust belt? Yes, and factories have opened in places like South Carolina and Alabama. According to data from the St. Louis Fed, manufacturing has stayed in a range of 11.3 percent to 13.6 percent of GDP since 1947. Manufacturing jobs have been replaced not by trade, but by technology. They have gone the same way as agricultural jobs. The fact that very few Americans work on farms does not mean that we are not producing food.

Once one understands that a trade deficit is not a bad thing, then she will understand why the word tariff is not in fact beautiful, no matter how many times Trump says it is. People want more for less, they want a trade deficit, and tariffs are not beautiful – but tariffs are in fact, as The Wall Street Journal has said, dumb. At least that is my perspective.

Warm regards,

Chuck Osborne, CFA

The opinions expressed on this blog are solely those of the author and not those of AssuredPartners Investment Advisors (APIA).

~More for Less

Sometime in the early 1970s my family visited my uncle and aunt in Bethesda, MD. My uncle, who was a congressman from North Carolina, showed us the sights. We did all of the usual DC tours – The White House, the Capitol, and the museums, but he also took my father into one of the government office buildings. They got on an elevator and stopped at a floor covered with desks and no walls; there was a government employee at every single desk.

My uncle asked my father to guess what they all did. Of course, my father had no idea. My uncle told him, “They do nothing. This is where they send the troublemakers. They can’t be fired, but no one wants them, so they come here and collect their checks.” That is what our government had grown into 50 years ago.

I believe we all understand intuitively that within any organization as large as the United States federal government, there is a certain amount of waste and inefficiency. Corporate America has a profit incentive to be as efficient as possible and this still happens there as well. We all know it, and most of us have personally experienced it; thus, the mission of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is a popular one. However, in life it is often not what you do, but how you do it.

I’m reminded of a scene from “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix,” when Kingsley Shacklebolt said to Cornelius Fudge, “You may not like him, Minister, but you can’t deny Dumbledore’s got style.” Well, you either love him or hate him, but either way you have to admit Donald Trump has style…or at least a style. He doesn’t just build hotels; he builds hotels with his name plastered on them in huge gold letters. He has been this way his whole life. So, he is not just going to quietly go about the business of rightsizing government the way it has been done by multiple administrations in the past. No, he is going to appoint the most successful businessman in America today, who happens to be a divisive character himself, to go in with a gold-plated sledgehammer.

So, should we be scared? The administration’s opponents want us to be scared. The short answer is, of course not. My favorite fear tactic this time is, “The unelected billionaire Elon Musk has access to our most personal information.” This refers to DOGE’s review of Treasury operations, and it sounds really scary, but let’s break it down.

Unelected: That describes every single individual at the U.S. Treasury department. It does today, and it has since the beginning of the U.S. Treasury. Nothing scary.

Billionaire: Put another way would be, “Really successful person who in this case has built and run some of the most innovative companies in the world.” Don’t get me wrong; If one wants to point at Sam Walton’s children and say, “You didn’t earn that,” then fair enough. One could also point to a certain currency trader and say, “You did that by gambling with other people’s money.” Also, fair enough. Elon Musk, however, earned his by knowing how to build large, efficient organizations. This should be a compliment.

Access to our most personal information: No more so than innumerable other government employees. If one is afraid of government having information about the citizens of the country, then he or she must logically be in favor of reducing the power and scope of government. That is DOGE’s mission.

None of the fear mongering passes even the most basic scrutiny, but it is part of the chaos that follows Donald Trump. Theodore Roosevelt said, “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.” Trump, on the other hand, carries a big stick and tells you that it is actually a huge, huge, fantastic, fantastically huge stick; he waves it around recklessly, and then finally sits down and talks softly. He doesn’t quietly go to our neighbors to the North and South and say, “Hey fellas, how about helping out with the fentanyl smuggling into the U.S.?” He announces a 25 percent across the board tariff and doesn’t even give them time to respond. Then he puts his stick down and starts to talk.

At the end of the day, DOGE is not doing anything that doesn’t need doing from time to time, and the tariffs are mostly bark with little bite. Our history is full of examples of the pendulum swinging from government growing to needing to be trimmed back, and all administrations negotiate with other countries. This administration just does it all with style. You might not like him, but you can’t deny Trump’s got style. He is the master of chaotic flamboyance. At least that is my perspective.

Warm regards,

Chuck Osborne, CFA

~The Master of Chaotic Flamboyance

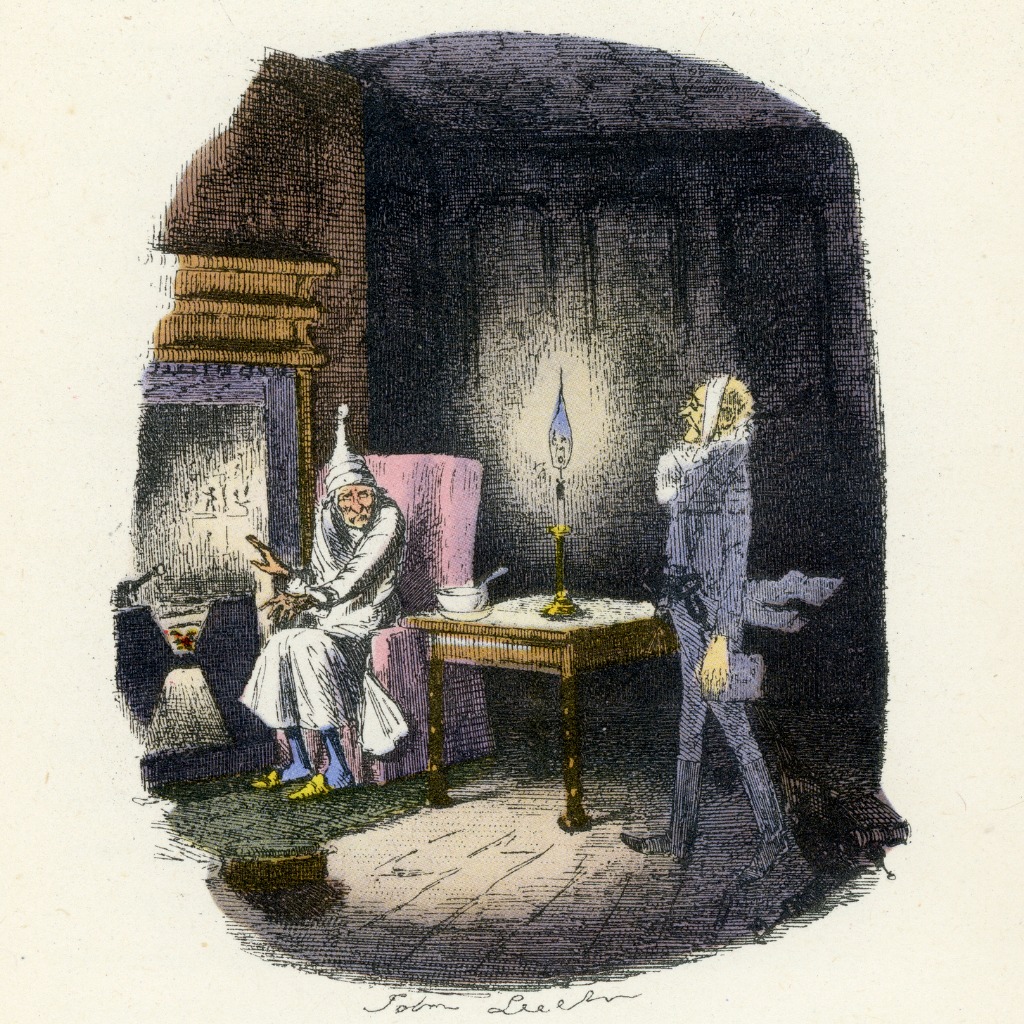

“Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, benevolence, were all my business. The dealings of my trade were but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of my business!”

~ Charles Dickens, “A Christmas Carol”

I get in trouble a lot. I don’t mean to, it just happens. I write and talk about economic issues because they impact daily life and the welfare of our clients. The “dealings of my trade” are to maximize the financial welfare of our clients. Maximizing economic growth is part of that equation, which means when I discuss economic policies I will point out when they actually hurt the economy, and that is what gets me in trouble. I get in trouble with Trump supporters when I point out that tariffs do far more damage than good, and I get in trouble with liberals when I point out that high levels of regulation are directly correlated to high levels of inequality. These economic realities run counter to their political preferences.

For a long time I struggled with how to respond in those situations, then one day when I was giving a talk to some clients in South Florida, someone rebuked me who did not like that I had just poked many holes in the Affordable Care Act. Without thinking I said, “There is more to life than economics. It is perfectly okay to argue that the economic sacrifice is worth it.” We all know this, and most of us practice it in our daily lives.

I coached youth basketball for years. That was an economic sacrifice, but the founding of One Atlanta Basketball and the young lives we influenced was rewarding in ways no amount of money could possibly replace. I also got to coach my own son and several of his teammates who now play together on their high school varsity team. When my daughter refused to play basketball but still insisted on her father coaching her team, I learned the game of soccer. More challenging, I learned how to coach girls. When I decided to hang the whistle up for good, my daughter understood but her teammates didn’t, and they shamed me into coaching one last season. Believe me, I know there is more to life than economics.

Nowhere is this more true than in international trade. Trade agreements are about a lot more than economics. I recall Trump’s first administration when he often disparaged existing trade agreements with China as being overly friendly to China. I will admit that I am no expert on the details of trade agreements with China, but Trump’s description seemed logical to me. Richard Nixon opened China to the West in 1972. We were in the midst of the Cold War; what better way to isolate the Soviet Union than to make the world’s largest communist country reliant on U.S. and European consumers for its welfare. One does not have to be an expert on the details to understand that there was more going on than just trade. It would be perfectly reasonable if the negotiators purposely made overly friendly agreements in an effort to make China more friendly to the West than they were to their fellow communist. It is also possible that Trump was correct and these agreements were just negotiated by really bad negotiators, but I prefer to give people the benefit of the doubt.

This leads to a question I keep pondering: Does Trump love tariffs because he lacks an understanding of economics, or because the lifelong negotiator understands the eminent leverage of the U.S. consumer? The United States remains the strongest economic force in our world. It is often said that when the U.S. economy sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold. One needs to look no farther than the inflation we have seen over the last four years: It started here with an ill-advised spending spree and then spread to the rest of the world. Trump understands that access to U.S. markets is a powerful carrot, and therefore any limitation on that access, such as tariffs, becomes a powerful stick.

When Trump threatens Mexico and Canada with tariffs, he is negotiating. This time he is not even trying to hide it. This is important for investors to understand because like many negotiators, the talk is always more extreme than the reality. Markets tend to react to headlines, but good investors know that it is reality that matters. Pay more attention to what is actually done, than to what is said.

We will hear a lot about tariffs over the next four years. I suspect we will hear about more tariffs than we actually see. I could be mistaken; it wouldn’t be the first time. But it seems to me that when Trump speaks of tariffs, fair trade is but a drop of water in the comprehensive ocean of geo-political negotiation. At least that is my perspective.

Warm regards,

Chuck Osborne, CFA

The opinions expressed on this blog are solely those of the author and not those of AssuredPartners Investment Advisors (APIA).

~Mankind Was My Business

I might be in the minority here, but this presidential election season seems more taxing than most. I really wish there was an interesting, or even realistic, tax proposal I could dissect for you all, but nope. All we are getting is “red meat” for the bases.

The Harris proposal includes raising corporate taxes. This sounds wonderful: Let those greedy corporations pay all the taxes. The problem with this in practice is that corporations are purely legal entities. Where does the money come from? The revenue for corporations comes from you and me and all the other consumers out there. The corporations’ expenses include buildings and equipment, etc., but the largest expense in almost every corporation is payroll. Their money comes from consumers and goes primarily to workers.

When taxes are raised on a corporation, their first impulse will be to pass on the expense to consumers. I know in our political fantasyland corporations can just raise prices whenever they want, but in the real world, prices are determined by supply and demand. Corporations can raise prices, but then they will sell less product, so that doesn’t automatically lead to higher revenue. Corporations cannot just raise prices to pay the tax and stay in business, so they must cut other expenses. What is their largest expense item? Payroll.

If you do believe that all corporations are run by greedy individuals, you have plenty of evidence to support that belief. Whose salary do you think will get cut to pay those taxes? If you guessed the rank-and-file employees, then you would be mostly correct. A good business (and they are out there) might spread it evenly, but even then, the rank and file are getting hit. Corporate tax is a tax on workers.

When the Trump administration cut corporate taxes, two things happened that may be counterintuitive to the non-economist. First, tax revenue from corporations actually increased. As we pointed out in our Quarterly Report from the third quarter of 2010, taxes work like prices: It is certainly possible to raise rates and collect less as well as to lower rates and collect more. Secondly, we had real wage growth and for the first time this century, most economic growth benefitted the middle class. Corporate tax cuts benefitted the people most economists said they would, and that was the rank-and-file employee.

The more traditional argument against the corporate tax still holds true: The corporate tax is by definition a double tax. Follow the money: Corporations get revenue from consumers who pay for the products with money that has been taxed, and they almost always have to pay an additional tax on the sale of the product. Then, the revenue is used to pay employees, each of whom must pay taxes on that money. Any money left over is often distributed to shareholders as a dividend, which is also taxed. All of this money is already taxed at least once. The corporate tax is a double dip.

On the other side, Trump has proposed not taxing Social Security or tips. On that note, should this pass, Iron Capital and AssuredPartners Investment Advisors will be amending our contracts, changing “investment management fee” to “suggested gratuity.” Yes, that is a joke, but so is arbitrarily excluding a certain form of income from the income tax.

The proposals from both campaigns are so bad that it might be easier to think about what a good tax system would look like. The goal of an ideal tax system would be to fully fund the government while having the least amount of impact on the economy as a whole. This is actually what was attempted in the 1980s. The tax reform acts of 1982 and 1986 were exactly that – reform. Yes, the highest nominal rate went from 70 percent to 28 percent, but with that went a massive closure of tax shelters. This is exactly what all should want: An honest tax rate that all people actually pay, each paying their fair share.

Politicians, on the other hand, love high rates. High rates create an incentive to find loopholes, and loopholes are paid for through political contributions. Economists refer to this as rent seeking. Restaurant owners will make significant political contributions to keep tip wages tax-free, and corporations will make significant contributions to avoid having to pay those sky-high corporate tax rates.

The first tax that I am aware of was proposed by Joseph to the Pharoah. Joseph understood the Pharoah’s dream to mean there would be seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine. Joseph suggested a 20 percent tax: 20 percent of the harvest was stored in grain houses so that when the famine hit, Egypt could care for its people. To our knowledge there were no loopholes or exemptions; everyone paid their fair share. Interestingly, approximately 20 percent of total economic output is what governments through time have been able to sustainably collect. It has not mattered what the stated rates are, or the overall structure of the tax systems.

I would love to be able to tell you that one of the presidential campaigns had a better overall tax policy, but that is not clear at all. Both campaigns seem eager to use the tax system to benefit specific groups over everyone else. That is certainly the incentive of any politician. We would have a much better economy and frankly a fairer world if they stopped playing these games, at least that is my perspective.

Meanwhile, we will be researching non-corporate business structures and pure gratuity business models…got to cover all of our bases.

Warm regards,

Chuck Osborne, CFA

Managing Director

~This is Taxing